Course Read/View-Along: Emdin's Reality Pedagogy

How the Emdin's "7 C's" shape my church & seminary teaching

There are some excellent religious education programs in American theological institutions. But since my specialty was learning, faith, and media, when I was thinking about returning to grad school I decided I had the best chance of being challenged and supported in a secular education program rather than a theology program. That's how I ended up at Teachers College.

I think this was a really good choice for me. It seems that a big part of my vocation is having one foot in two different worlds and trying to help members of one of those worlds make sense of the other. There are lots of ampersands in the intellectual life of Kyle Oliver. When I was in grad school the first time around, it was engineering & education. In seminary, I focused on science & theology. And these days my focus is secular education & Christian formation.

In some ways, this "translation" work was very straightforward. One of my professors figured out very quickly how my experience in seminaries was analogous to their experience in a graduate school of education. "We do teacher education. Kyle does minister education."

But the big thing I've puzzled with over the years is that so much of teacher education is focused on in-school, K–12-style learning. And a big part of the religious educational project in the late-20th and early-21st centuries (at least in Mainline Protestant circles) has been to try to free ourselves from the schooling paradigm of Christian formation.

The situation is not as mismatched as it seems. First of all, there are lots of "out of school" learning specialists at Teachers College, and I tended to gravitate to their courses and research labs.

Moreover, the legacy of No Child Left Behind, high-stakes testing, and other confining regimes has made it quite hard to do innovative research and practice in traditional K–12 classroom settings. "I'll probably start an after school program or go work for a charter school" is what I heard from classmates over and over again—and not because they don't love public education. Those venues are simply where it feels like education can breathe a little.

But I digress. Because the truth is, the cliché "good teaching is good teaching" is a cliché for a reason, and plenty of the ideas that classroom researchers are chewing on can be applicable in out-of-school (or should I say out-of-Sunday-school?) settings.

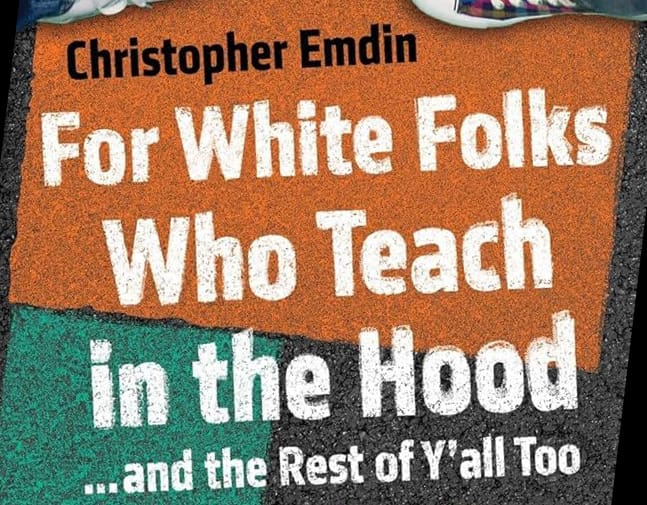

This is all preamble to say that anyone reading this post can benefit from doubling down on what science education scholar Chris Emdin puts after the ellipsis in the title of his book For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood ... and the Rest of Y'all Too.

If you want an intro to Emdin's thinking, I highly recommend this TEDx talk—often one of the highlights of the semester for my students in Adapting Christian Formation:

In the second half of the video, Emdin dives into the framework he would later describe in more detail in the book. He calls it reality pedagogy. It is culturally specific, tailored to address the cultures, challenges, and opportunities in the urban education contexts Emdin cares most about.

What I thought might be valuable for this post is to share a little bit about some of "7 C's" of reality pedagogy—

- cogenerative dialogues,

- coteaching,

- cosmopolitanism,

- context,

- content,

- competition, and

- curation

—and how thinking about them a lot since encountering Professor Emdin in 2019 has shaped the commitments of my practice in both online seminary teaching and onsite Christian formation leadership.

Cogenerative dialogue should shape our learning spaces. Emdin uses the patterns of the hip hop cypher to convene conversation circles with his students. The goal of these circles is opening up authentic student feedback about what's working and what's not working in the culture of the classroom, with an eye toward co-creating new approaches. (This is especially important when there's likely to be a major teacher / student or academic culture / student culture disconnect.)

Since reading Emdin, I am much more likely to press pause and take the pulse of participants, in the middle of the semester or in the middle of an activity. "Something's not working here, so how can we fix it?" is a really powerful question for any leader to ask.

Scary too, because we might find the answer challenging. That's usually a sign that the process is working. Note also that focusing on that process is important, because students don't always feel safe to share what they need without some guardrails in place.

Cosmopolitanism means everyone has a role to play—and we miss you when you're gone. A post like this doesn't have space to dive way into this philosophical school for what it means to be a community amid difference. For Emdin, it means students in the classroom gets assigned different tasks, and the class depends on each student to function well. For example ,when the Board Eraser is absent, the class has to figure out together a way to make do without the board getting erased.

At the church where I attend and volunteer, we're starting to look for more ways for our young people to play age-appropriate roles during the service, beyond just having a couple of child acolytes, youth readers or ushers, etc. I love the idea of there being some roles that are especially for kids. When none (or not enough) are present, then those parts of our worship just don't happen. In those moments, we know that the community is stronger when we're all together.

Curation acknowledges the communal nature of knowledge, expertise, identity. The art of curating resources had a buzzy moment in the mid-'10s, when social networking gave everyone a platform (if they wanted it) to make product recommendations, write restaurant reviews, etc. Emdin writes a lot about what it means to make space for young people as cultural curators to bring their everyday passion and expertise to the classroom. (Recall this post on the funds of knowledge tradition.)

When I was first coming up in formation, the Journey to Adulthood program was pretty universally agreed to be on the cutting edge of youth ministry and confirmation prep. They used J2A at one of the churches where I did field ed in seminary, and I can still remember what the church looked like when the "Rite 13" students made posters to name and proclaim "Who I Am" and lined the nave with them, temporarily upstaging all the beautiful stained glass windows and other formal liturgical art.

When we give learners the chance to share and geek out about the media, hobbies, and other everyday objects and activities that shape their worlds, we show them what we too often just say we believe: that their culture and identity are a blessing to themselves and others.

**

I really can't recommend this book enough to anyone who wants to think carefully about culture and community in education, regardless of the current racial diversity of the communities you serve.

What Emdin and so many scholars of modern education know is that a sense of belonging is often what is missing for students who don't thrive in traditional academic settings. I think there are a ton of directly analogous lessons for those of us who care about helping people thrive in church settings.