Practice (+ Context) Makes Perfect

Helping your brain make dense, relevant connections

Today I want to shout out a terrific writing center blog post by Claire Hoogendoorn I stumbled across almost three years ago. It brings together a few different strands of learning science that I think are especially important to this week's theme: practice.

Perhaps you've learned the hard way what it's like to think we know something but not to have practiced it enough to execute when the rubber meets the road.

At one far extreme of this phenomenon might be something like sports analysis. I think of David Foster Wallace's transcendent tennis send-ups. I could take in some serious "how-to" from a piece like "Roger Federer as Religious Experience," but it wouldn't mean a damn for me on the court without literally thousands of hours of practice, preferably at about the age of ten.

Put me in a match and I could "know" fully well how to hit a serve or groundstroke or drop shot without actually possessing the relevant skill. And that's not the half of it, because a player has to know how to string all these kinds of shots together in graceful and strategic ways that are responsive to particular scenarios in the rally and the match as a whole.

But we're really not just talking about kinesiological forms of learning here. I can rattle off the Pythagorean Theorem, the definition of a dangling modifier, or the phases of mitosis without being able to explain or apply this knowledge in a meaningful way. We need to practice solving for b in a couple dozen geometry problems or parsing a West Wing season's worth of dangling modifier jokes to use this information successfully.

(Why no mitosis example? Because I didn't practice enough and have no earthly idea how to illustrate the biological importance of mitosis. I couldn't even have told you the difference between it an meiosis without the Wikipedia page. They're just marginally connected words from a shaky high school memories, along with metonymy, Hobbes' Leviathan, and the year 1066.)

We probably all have this sense that practice is key to learning, as well as a temptation to cheat on practice even though we know better. But what's the underlying science here? And can it tell us anything? I think so.

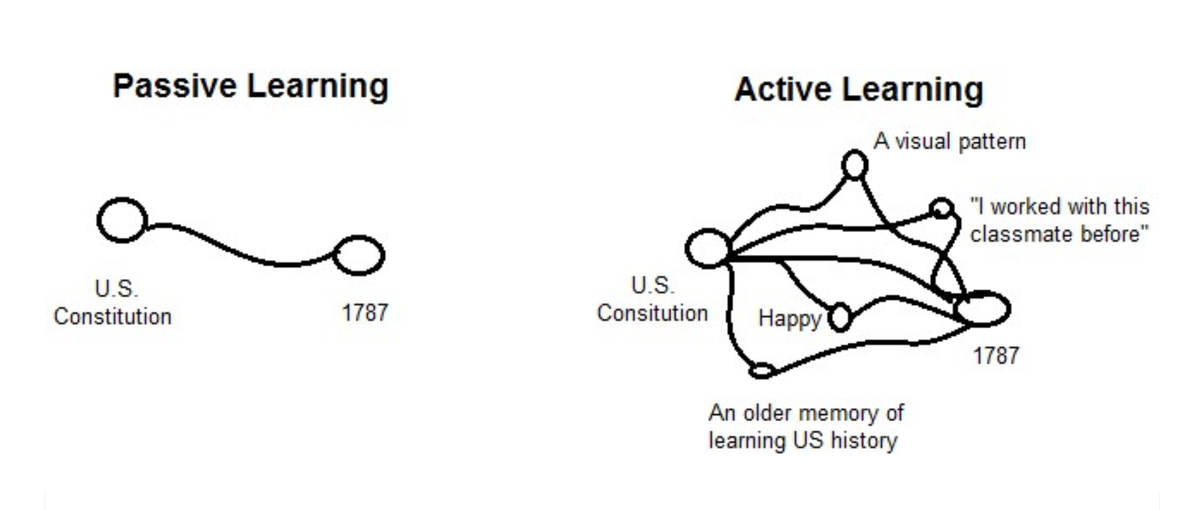

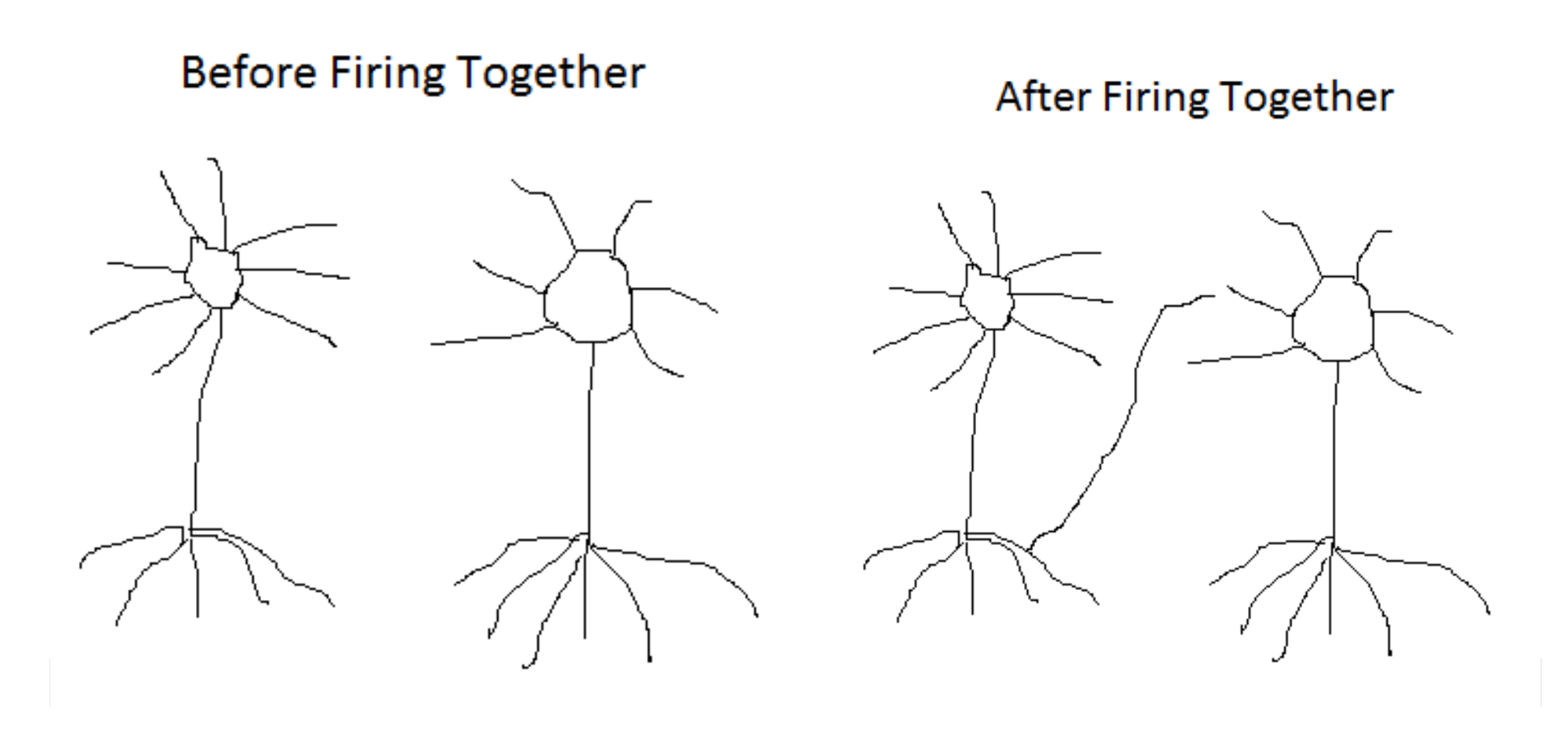

When new knowledge connects to old knowledge (remember constructivism?) unrelated neurons start forming a tenuous new connection. With enough reinforcement, the connection strengthens. This is called Hebb's Rule.

The reason we should practice is that we need to add not just a new connection but new complexity to the changing neural network. And doing so requires particular kinds of practice, says Hoogendoorn—practice with lots of rich variety:

By approaching a topic in multiple ways, students can integrate class content by activating a variety of different interconnected brain processes (e.g., writing, listening, speaking, interacting, moving, etc).

Isolated facts or data do not, by themselves, contribute meaningfully to our practical knowledge and skill. But complex webs of meaning start to form the basis of more sophisticated knowledge and skill over time, with practice.

We can connect multiple familiar concepts with multiple new concepts, preferably via a little doodle in our notes, and later a written post to the course discussion forum, and later an impromptu explanation to a friend or colleague, etc. Some of this practice might even be thrust upon us, as life queues up little opportunities to recall and reconsider something we've previously learned.

The little sketch at the very top of the post gives you a sense of the kinds of connections that might form through this kind of varied practice.

Does it matter than you come to associate not only the year 1787 with the U.S. constitution but also with a feeling of happiness or the familiarity of having worked with a course project classmate before? Maybe, maybe not. But better to form excess connections than inadequate connections.

I hope this gives you some sense of why (and how!) to practice when you're trying to learn something new. On Wednesday, I'll have a few thoughts (courtesy of the author of Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat) on how to cope when we haven't had the chance to practice.